Artificial insemination

| Artificial insemination | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

| ICD-9-CM | 69.92 |

| MeSH | D007315 |

Artificial insemination, or AI, is the process by which sperm is placed into the reproductive tract of a female for the purpose of impregnating the female by using means other than sexual intercourse or natural insemination. In humans, it is used as assisted reproductive technology, using either sperm from the woman's male partner or sperm from a sperm donor (donor sperm) in cases where the male partner produces no sperm or the woman has no male partner (i.e., single women, lesbians). In cases where donor sperm is used the woman is the gestational and genetic mother of the child produced, and the sperm donor is the genetic or biological father of the child.

Artificial insemination is widely used for livestock breeding, especially for dairy cattle and pigs. Techniques developed for livestock have been adapted for use in humans.

Specifically, freshly ejaculated sperm, or sperm which has been frozen and thawed, is placed in the cervix (intracervical insemination – ICI) or, after washing, into the female's uterus (intrauterine insemination – IUI) by artificial means.

In humans, artificial insemination was originally developed as a means of helping couples to conceive where there were 'male factor' problems of a physical or psychological nature affecting the male partner which prevented or impeded conception. Today, the process is also and more commonly used in the case of choice mothers, where a woman has no male partner and the sperm is provided by a sperm donor.

Contents |

In humans

Preparations

A sperm sample will be provided by the male partner of the woman undergoing artificial insemination, but sperm provided through sperm donation by a sperm donor may be used if, for example, the woman's partner produces too few motile sperm, or if he carries a genetic disorder, or if the woman has no male partner. Sperm is usually obtained through masturbation or the use of an electrical stimulator, although a special condom, known as a collection condom, may be used to collect the semen during intercourse.

The man providing the sperm is usually advised not to ejaculate for two to three days before providing the sample in order to increase the sperm count.

A woman's menstrual cycle is closely observed, by tracking basal body temperature and changes in vaginal mucus, or using ovulation kits, ultrasounds or blood tests.

When using intrauterine insemination (IUI), the sperm must have been “washed” in a laboratory and concentrated in Hams F10 media without L-glutamine, warmed to 37C.[1] The process of “washing” the sperm increases the chances of fertilization and removes any mucus and non-motile sperm in the semen. Pre and post concentration of motile sperm is counted.

If sperm is provided by a sperm donor through a sperm bank, it will be frozen and quarantined for a particular period and the donor will be tested before and after production of the sample to ensure that he does not carry a transmissible disease. Sperm samples donated in this way are produced through masturbation by the sperm donor at the sperm bank. A chemical known as a cryoprotectant is added to the sperm to aid the freezing and thawing process. Further chemicals may be added which separate the most active sperm in the sample as well as extending or diluting the sample so that vials for a number of inseminations are produced. For fresh shipping, a semen extender is used.

If sperm is provided by a private donor, either directly or through a sperm agency, it is usually supplied fresh, not frozen, and it will not be quarantined. Donor sperm provided in this way may be given directly to the recipient woman or her partner, or it may be transported in specially insulated containers. Some donors have their own freezing apparatus to freeze and store their sperm. Private donor sperm is usually produced through masturbation, but some donors use a collection condom to obtain the sperm when having sexual intercourse with their own partners.

Procedure

When an ovum is released, semen provided by the woman's male partner, or by a sperm donor, is inserted into the woman's vagina or uterus. The semen may be fresh or it may be frozen semen which has been thawed. Where donor sperm is supplied by a sperm bank, it will always be quarantined and frozen and will need to be thawed before use. Specially designed equipment is available for carrying out artificial inseminations.

In the case of vaginal artificial insemination, semen is usually placed in the vagina by way of a needleless syringe. A longer tube, known as a 'tom cat' may be attached to the end of the syringe to facilitate deposit of the semen deeper into the vagina. The woman is generally advised to lie still for a half hour or so after the insemination to prevent seepage and to allow fertilization to take place.

A more efficient method of artificial insemination is to insert semen directly into the woman's uterus. Where this method is employed it is important that only 'washed' semen be used and this is inserted into the uterus by means of a catheter. Sperm banks and fertility clinics usually offer 'washed' semen for this purpose, but if partner sperm is used it must also be 'washed' by a medical practitioner to eliminate the risk of cramping.

Semen is occasionally inserted twice within a 'treatment cycle'. A double intrauterine insemination has been theorized to increase pregnancy rates by decreasing the risk of missing the fertile window during ovulation. However, a randomized trial of insemination after ovarian hyperstimulation found no difference in live birth rate between single and double intrauterine insemination.[2]

An alternative method to the use of a needless syringe or a catheter involves the placing of partner or donor sperm in the woman's vagina by means of a specially designed cervical cap, a conception device or conception cap. This holds the semen in place near to the entrance to the cervix for a period of time, usually for several hours, to allow fertilization to take place. Using this method, a woman may go about her usual activities while the cervical cap holds the semen in the vagina. One advantage with the conception device is that fresh, non-liquified semen may be used.

If the procedure is successful, the woman will conceive and carry to term a baby. The baby will be the woman's biological child, and the biological child of the man whose sperm was used to inseminate her, whether he is the woman's partner or a donor. A pregnancy resulting from artificial insemination will be no different from a pregnancy achieved by sexual intercourse. However, there may be a slight increased likelihood of multiple births if drugs are used by the woman for a 'stimulated' cycle.

Donor variations

Either sperm provided by the woman's husband or partner (artificial insemination by husband, AIH) or sperm provided by a known or anonymous sperm donor (artificial insemination by donor, AID or DI) can be used.

Techniques

Intrauterine insemination, Intravaginal insemination, Intracervical insemination, and Intratubal insemination

Intracervical insemination

ICI is the easiest way to inseminate. This involves the deposit of raw fresh or frozen semen (which has been thawed) by injecting it high into the cervix with a needle-less syringe. This process closely replicates the way in which fresh semen is directly deposited on to the neck of the cervix by the penis during vaginal intercourse. When the male ejaculates, sperm deposited this way will quickly swim into the cervix and toward the fallopian tubes where an ovum recently released by the ovary(s) hopefully awaits fertilization. It is the simplest method of artificial insemination and 'unwashed' or raw semen is normally used. It is probably therefore, the most popular method and is used in most home, self and practitioner insemination procedures.

Timing is critical as the window and opportunity for fertilization, is little more than 12 hours from the release of the ovum. For each woman who goes through this process be it AI (artificial insemination) or NI (natural insemination); to increase chances for success, an understanding of her rhythm or natural cycle is very important. Home ovulation tests are now available. Doing and understanding Basal Temperature Tests over several cycles; there is a slight dip and quick rise at the time of ovulation. She should note the color and texture of her vaginal mucous discharge. At the time of ovulation the protective cervical plug is released giving the vaginal discharge a stringy texture with an egg white color. A woman may also be able check the softness of the nose of her cervix by inserting two fingers. It should be considerably softer and more pliable than normal.

Advanced technical (medical) procedures may be used to increase the chances of conception.

When performed at home without the presence of a professional this procedure is sometimes referred to as intravaginal insemination or IVI.[3]

Intrauterine insemination

'Washed sperm', that is, spermatozoa which have been removed from most other components of the seminal fluids, can be injected directly into a woman's uterus in a process called intrauterine insemination (IUI). If the semen is not washed it may elicit uterine cramping, expelling the semen and causing pain, due to content of prostaglandins. (Prostaglandins are also the compounds responsible for causing the myometrium to contract and expel the menses from the uterus, during menstruation.) The woman should rest on the table for 15 minutes after an IUI to optimize the pregnancy rate.[4]

To have optimal chances with IUI, the female should be under 30 years of age, and the man should have a TMS of more than 5 million per ml.[5] In practice, donor sperm will satisfy these criteria. A promising cycle is one that offers two follicles measuring more than 16 mm, and estrogen of more than 500 pg/mL on the day of hCG administration.[5] A short period of ejaculatory abstinence before intrauterine insemination is associated with higher pregnancy rates.[6] However, GnRH agonist administration at the time of implantation does not improve pregnancy outcome in intrauterine insemination cycles according to a randomized controlled trial.[7]

It can be used in conjunction with ovarian hyperstimulation. Still, advanced maternal age causes decreased success rates; Women aged 38–39 years appear to have reasonable success during the first two cycles of ovarian hyperstimulation and IUI. However, for women aged ≥40 years, there appears to be no benefit after a single cycle of COH/IUI.[8] It is therefore recommended to consider in vitro fertilization after one failed COH/IUI cycle for women aged ≥40 years.[8]

Intrauterine tuboperitoneal insemination

Intrauterine tuboperitoneal insemination (IUTPI) is insemination where both the uterus and fallopian tubes are filled with insemination fluid. The cervix is clamped to prevent leakage to the vagina, best achieved with the specially designed Double Nut Bivalve (DNB) speculum. The sperm is mixed to create a volume of 10 ml, sufficient enough to fill the uterine cavity, pass through the interstitial part of the tubes and the ampulla, finally reaching the peritoneal cavity and the Pouch of Douglas where it would be mixed with the peritoneal and follicular fluid. IUTPI can be useful in unexplained infertility, mild or moderate male infertility, and mild or moderate endometriosis.[9]

Intratubal insemination

IUI can furthermore be combined with intratubal insemination (ITI), into the Fallopian tube although this procedure is no longer generally regarded as having any beneficial effect compared with IUI.[10] ITI however, should not be confused with gamete intrafallopian transfer, where both eggs and sperm are mixed outside the woman's body and then immediately inserted into the Fallopian tube where fertilization takes place.

Pregnancy rate

Success rates, or pregnancy rates for artificial insemination may be very misleading, since many factors including the age and health of the recipient have to be included to give a meaningful answer, e.g. definition of success and calculation of the total population.[11] For couples with unexplained infertility, unstimulated IUI is no more effective than natural means of conception.[12][13]

Generally, it is 10 to 15% per menstrual cycle using ICI, and[14] and 15-20% per cycle for IUI.[14] In IUI, about 60 to 70% have achieved pregnancy after 6 cycles.[15]

As seen on the graph, the pregnancy rate also depends on the total sperm count, or, more specifically, the total motile sperm count (TMSC), used in a cycle. It increases with increasing TMSC, but only up to a certain count, when other factors become limiting to success. The summed pregnancy rate of two cycles using a TMSC of 5 million (may be a TSC of ~10 million on graph) in each cycle is substantially higher than one single cycle using a TMSC of 10 million. However, although more cost-efficient, using a lower TMSC also increases the average time taken before getting pregnant. Women whose age is becoming a major factor in fertility may not want to spend that extra time.

Samples per child

How many samples (ejaculates) that are required give rise to a child varies substantially from person to person, as well as from clinic to clinic.

However, the following equations generalize the main factors involved:

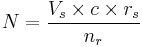

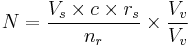

For intracervical insemination:

- N is how many children a single sample can give rise to.

- Vs is the volume of a sample (ejaculate), usually between 1.0 mL and 6.5 mL[16]

- c is the concentration of motile sperm in a sample after freezing and thawing, approximately 5-20 million per ml but varies substantially

- rs is the pregnancy rate per cycle, between 10% to 35% [14][17]

- nr is the total motile sperm count recommended for vaginal insemination (VI) or intra-cervical insemination (ICI), approximately 20 million pr. ml.[18]

The pregnancy rate increases with increasing number of motile sperm used, but only up to a certain degree, when other factors become limiting instead.

In the simplest form, the equation reads:

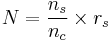

- N is how many children a single sample can give rise to

- ns is the number of vials produced per sample

- nc is the number of vials used in a cycle

- rs is the pregnancy rate per cycle

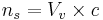

ns can be further split into:

- ns is the number of vials produced per sample

- Vs is the volume of a sample

- Vv is the volume of the vials used

nc may be split into:

- nc is the number of vials used in a cycle

- nr is the number of motile sperm recommended for use in a cycle

- ns is the number of motile sperm in a vial

ns may be split into:

- ns is the number of motile sperm in a vial

- Vv is the volume of the vials used

- c is the concentration of motile sperm in a sample

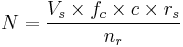

Thus, the factors can be presented as follows:

- N is how many children a single sample can help giving rise to

- Vs is the volume of a sample

- c is the concentration of motile sperm in a sample

- rs is the pregnancy rate per cycle

- nr is the number of motile sperm recommended for use in a cycles

- Vv is the volume of the vials used (its value doesn't affect N and may be eliminated. In short, the smaller the vials, the more vials are used)

With these numbers, one sample would on average help giving rise to 0.1-0.6 children, that is, it actually takes on average 2-5 samples to make a child.

For intrauterine insemination (IUI), a centrifugation fraction (fc) may be added to the equation:

- fc is the fraction of the volume that remains after centrifugation of the sample, which may be about half (0.5) to a third (0.33).

On the other hand, only 5 million motile sperm may be needed per cycle with IUI (nr=5 million)[17]

Thus, only 1-3 samples may be needed for a child if used for IUI.

History

In the 1980s, direct intraperitoneal insemination (DIPI) was occasionally used, where doctors injected sperm into the lower abdomen through a surgical hole or incision, with the intention of letting them find the oocyte at the ovary or after entering the genital tract through the ostium of the fallopian tube.[19][20]

Artificial insemination in livestock and pets

Artificial insemination is used in many non-human animals, including sheep, horses, cattle, pigs, dogs, pedigree animals generally, zoo animals, turkeys and even honeybees. It may be used for many reasons, including to allow a male to inseminate a much larger number of females, to allow use of genetic material from males separated by distance or time, to overcome physical breeding difficulties, to control the paternity of offspring, to synchronise births, to avoid injury incurred during natural mating, and to avoid the need to keep a male at all (such as for small numbers of females or in species whose fertile males may be difficult to manage).

Semen is collected, extended, then cooled or frozen. It can be used on site or shipped to the female's location. If frozen, the small plastic tube holding the semen is referred to as a straw. To allow the sperm to remain viable during the time before and after it is frozen, the semen is mixed with a solution containing glycerol or other cryoprotectants. An extender is a solution that allows the semen from a donor to impregnate more females by making insemination possible with fewer sperm. Antibiotics, such as streptomycin, are sometimes added to the sperm to control some bacterial venereal diseases. Before the actual insemination, estrus may be induced through the use of progestogen and another hormone (usually PMSG or Prostaglandin F2α).

Artificial insemination of farm animals is very common in today's agriculture industry in the developed world, especially for breeding dairy cattle. (75% of all inseminations) Swine are also bred using this method (up to 85% of all inseminations). It provides an economical means for a livestock breeder to improve their herds utilizing males having very desirable traits.

Although common with cattle and swine, AI is not as widely practised in the breeding of horses. A small number of equine associations in North America accept only horses that have been conceived by "natural cover" or "natural service" – the actual physical mating of a mare to a stallion. The Jockey Club being the most notable of these - no AI is allowed in Thoroughbred breeding.[21] Other registries such as the AQHA and warmblood registries allow registration of foals created through AI, and the process is widely used allowing the breeding of mares to stallions not resident at the same facility - or even in the same country - through the use of transported frozen or cooled semen.

Modern Artificial Insemination was pioneered by Dr. John O. Almquist of the Pennsylvania State University. His improvement of breeding efficiency by the use of antibiotics (first proven with penicillin in 1946) to control bacterial growth, decreasing embrionic mortality and increase fertiilty, and various new techniques for processing, freezing and thawing of frozen semen significantly enhanced the practical utilization of AI in the livestock industry, and earned him the [22] 1981 Wolf Foundation Prize in Agriculture. Many techniques developed by him have since been applied to other species, including that of the human male.

The,[23] John O. Almquist Dairy Breeding Research Center, at Penn State University, is a unique facility for research on reproduction in farm animals. It is one of only three centers worldwide providing substantial housing for mature bulls. The Center has a long-standing working relationship with the artificial insemination industry. Today we have a new methodology named "Barceló Method for Artificial Insemination" patented by Carlos Alberto Barceló Rojas from Villahermosa, Tabasco, México. It's a revolutionary method for impregnanting cows. Some cattleman are using it successfully in their farms located in the south of México with percentages over 90%. Patent Application WO/2011/034411

See also

- Semen extender

- Embryo transfer

- Ex-situ conservation

- Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- Sperm bank

- Sperm donation

- Accidental incest

- Sperm sorting

- Donor conceived people

- Surrogacy

- Frozen zoo

- Wildlife

- Conception device

- Ejaculation

Notes

- ^ Adams, Robert, M.D."invitro fertilization technique", Monterey, CA, 1988

- ^ Bagis T, Haydardedeoglu B, Kilicdag EB, Cok T, Simsek E, Parlakgumus AH (May 2010). "Single versus double intrauterine insemination in multi-follicular ovarian hyperstimulation cycles: a randomized trial". Hum Reprod 25 (7): 1684–90. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq112. PMID 20457669.

- ^ European Sperm Bank USA

- ^ Laurie Barclay. "Immobilization May Improve Pregnancy Rate After Intrauterine Insemination". Medscape Medical News. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/711566?src=mpnews&spon=16&uac=75071SJ. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Merviel P, Heraud MH, Grenier N, Lourdel E, Sanguinet P, Copin H (November 2008). "Predictive factors for pregnancy after intrauterine insemination (IUI): An analysis of 1038 cycles and a review of the literature". Fertil. Steril. 93 (1): 79–88. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.058. PMID 18996517.

- ^ Marshburn PB, Alanis M, Matthews ML, et al. (September 2009). "A short period of ejaculatory abstinence before intrauterine insemination is associated with higher pregnancy rates". Fertil. Steril. 93 (1): 286–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.972. PMID 19732887.

- ^ Bellver J, Labarta E, Bosch E, et al. (June 2009). "GnRH agonist administration at the time of implantation does not improve pregnancy outcome in intrauterine insemination cycles: a randomized controlled trial". Fertil. Steril. 94 (3): 1065–71. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.044. PMID 19501354.

- ^ a b Harris, I.; Missmer, S.; Hornstein, M. (2010). "Poor success of gonadotropin-induced controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination for older women". Fertility and sterility 94 (1): 144–148. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.040. PMID 19394605.

- ^ Leonidas Mamas, M.D.,Ph.D (March 2006). "Comparison of fallopian tube sperm perfusion and intrauterine tuboperitoneal insemination:a prospective randomized study". Fertility and Sterility Journal 85 (3): 735–740. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.08.025. PMID 16500346.

- ^ Hurd WW, Randolph JF, Ansbacher R, Menge AC, Ohl DA, Brown AN (February 1993). "Comparison of intracervical, intrauterine, and intratubal techniques for donor insemination". Fertil. Steril. 59 (2): 339–42. PMID 8425628.

- ^ IVF.com

- ^ Fertility treatments 'no benefit'. BBC News, 7 August 2008

- ^ Bhattacharya S, Harrild K, Mollison J, et al. (2008). "Clomifene citrate or unstimulated intrauterine insemination compared with expectant management for unexplained infertility: pragmatic randomised controlled trial". BMJ 337: a716. doi:10.1136/bmj.a716. PMC 2505091. PMID 18687718. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2505091.

- ^ a b c Utrecht CS News Subject: Infertility FAQ (part 4/4)

- ^ Intrauterine insemination. Information notes from the fertility clinic at Aarhus University Hospital, Skejby. By PhD Ulrik Kesmodel et al.

- ^ Essig, Maria G.; Edited by Susan Van Houten and Tracy Landauer, Reviewed by Martin Gabica and Avery L. Seifert (2007-02-20). "Semen Analysis". Healthwise. WebMD. http://www.webmd.com/infertility-and-reproduction/guide/semen-analysis?page=1. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ a b Cryos International - What is the expected pregnancy rate (PR) using your donor semen?

- ^ Cryos International - How much sperm should I order?

- ^ Oral Sex, a Knife Fight and Then Sperm Still Impregnated Girl. Account of a Girl Impregnated After Oral Sex Shows Sperms' Incredible Survivability By LAUREN COX. abcNEWS/Health Feb. 3, 2010

- ^ Cimino, C.; Guastella, G.; Comparetto, G.; Gullo, D.; Perino, A.; Benigno, M.; Barba, G.; Cittadini, E. (1988). "Direct intraperitoneal insemination (DIPI) for the treatment of refractory infertility unrelated to female organic pelvic disease". Acta Europaea fertilitatis 19 (2): 61–68. PMID 3223194.

- ^ The Jockey Club has never allowed artificial insemination.

- ^ 1981 Wolf Foundation Prize in Agriculture

- ^ John O. Almquist Dairy Breeding Research Center

References

- Hammond, John, et al., The Artificial Insemination of Cattle (Cambridge, Heffer, 1947, 61pp)

External links

- Detailed description of the different fertility treatment options available

- A history of artificial insemination

- What are the Ethical Considerations for Sperm Donation?

- United States state court rules sperm donor is not liable for children

- UK Sperm Donors Lose Anonymity

- AI technique in the equine

- IntraUterine TuboPeritoneal Insemination (IUTPI)

- The Hastings Center's Bioethics Briefing Book entry on assisted reproduction

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||